Beyond Abstraction: Using Design Theory to Understand Tabletop Wargames

A deeper look two frameworks that help designers and hobbyists better understand how rules create experience in games. Also my humble attempt to make sense of them in table top wargaming.

From Abstraction to Frameworks

In a recent article, I argued that abstraction—the art of compressing messy reality into workable rules—is the essential craft behind every tabletop system. While chasing sources on that topic, I encountered two design frameworks that sharpened my thinking overnight: Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics (MDA) and its successor, Design, Dynamics, and Experience (DDE).

As a learning designer, I had come across MDA in passing during discussions about gamification in digital learning. However, re-engaging with these models in the context of tabletop gaming challenged the way I think and talk about game design.

We can all agree frameworks represent ways to clarify what’s working, what isn’t, and why. In no way am I suggesting this is a new thing; for all I know, tabletop wargame designers do engage with these models already. This article aims to (a) introduce the MDA and DDE frameworks possibly to those outside game design, (b) explain why DDE evolved from MDA, and (c) show how the pair can enrich discussion around games using the popular and well-known game Warhammer 40,000 as an example. Consider it an invitation to add a useful tool to your design or player toolkit.

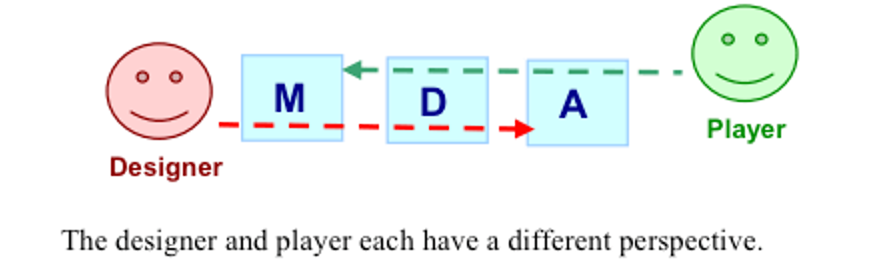

A Primer on MDA

Let's begin by understanding the foundational MDA framework.

The Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics (MDA) framework was introduced in 2004 by Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc, and Robert Zubek in their paper, “MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research.” It proposed a shared vocabulary to connect designers, researchers, and critics. Because it’s easy to remember, MDA spread widely across the games industry, cited in everything from Ubisoft’s design discussions for Rainbow Six: Siege to academic studies on simulation-based learning.

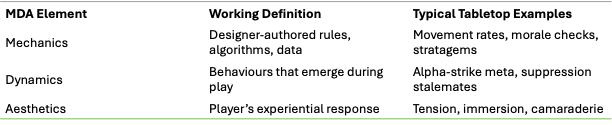

Table 1: The MDA Framework with examples from tabletop wargaming

However, after two decades of use, designers and players pointed to several limitations. The term “Mechanics” grew too broad, while “Aesthetics” was frequently misunderstood as visual design or graphics instead of its intended meaning: the player’s emotional experience. These tensions opened the door for a revised approach.

Enter DDE: Design, Dynamics, Experience

Recognising these limitations, the DDE framework was introduced.

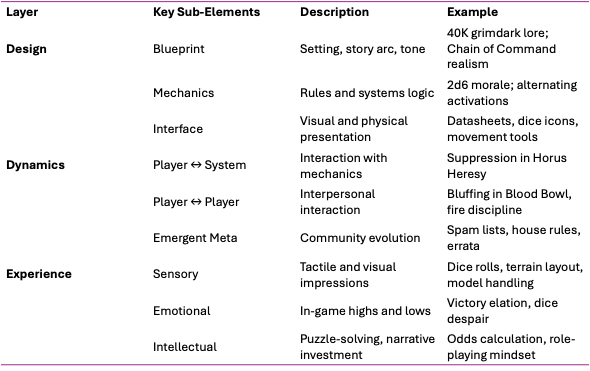

In 2016, Wolfgang Walk and colleagues introduced DDE as an evolution of MDA. They retained the core causal chain—Design → Dynamics → Experience—but expanded each layer to better reflect how modern games work.

Design includes all elements authored before play begins, such as rules, art, scenarios, and lore. It explicitly includes narrative structures, worldbuilding, and the visual and physical expression of the game, clarifying areas MDA left ambiguous.

Dynamics cover what unfolds when players engage the system, such as strategy loops, house rules, and social metagames. DDE also casts dynamics as potential narrative drivers—emergent storytelling shaped by player input and systemic conflict.

Experience represents what players feel, process, and remember, from the tactical joy of a successful maneuver to the frustration of a bad dice roll. DDE breaks this down into sensory, emotional, and intellectual journeys, foregrounding the player's full arc through gameplay.

Table 2: Expanded DDE elements, descriptions, and examples

This increased granularity directly addresses MDA’s weaknesses, especially the misinterpretation of ‘Aesthetics’. The DDE model provides a more detailed catalogue of elements, allowing for more targeted fixes (e.g., is an overpowered "alpha strike" a Mechanics or Interface issue?) and helping align a game's story with its rules.

Why a Common Language Accelerates Problem-Solving

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” — Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921)

Good frameworks shrink the gap between symptom and cause. By giving us a shared language, DDE allows a group to move past subjective debate and toward constructive diagnosis. When a playtester can say, “This Design choice creates a negative Dynamic that undermines the intended Experience,” the path to a solution becomes much clearer. This leads to faster diagnostics and better alignment between designers, writers, and players.

Framework in Action: A Case Study of Warhammer 40,000

To illustrate DDE clearly, let's consider a specific example.

Using Games Workshop’s Warhammer 40,000 (10th Edition), we trace connections from a specific design choice to the actual player experience. Let’s analyze a common phenomenon: the "alpha strike," where a player attempts to neutralize their opponent with an overwhelming first-turn attack. Please note this is my interpretation and not a definitive analysis.

First, we identify core Design elements:

Mechanics: Keyword-driven datasheets with highly lethal weapon profiles and rules allowing all unit activations before opponent response.

Interface: Guidelines on terrain that might not enforce sufficient line-of-sight blocking terrain.

Next, we observe emergent Dynamics:

High lethality of unit stats and rule combinations, combined with turn structure creates a powerful incentive for decisive first-turn attacks, fostering an "alpha-strike meta." Sparse terrain enhances this issue.

Finally, we analyse the resulting player Experience:

Emotionally, the attacker experiences empowerment, while the defender faces intense frustration due to premature defeat.

Intellectually, the game shifts from mid-game tactics to pre-game list building, diminishing mid-game depth. Terms such as List Hammer or Math Hammer frequently arise where players seek to optimise their lists before the game.

Using DDE diagnostically, we see clearly how adjusting Mechanics (unit lethality, turn sequence) or Interface (terrain rules) could offer a way to address the negative Dynamic and restore intended player Experience. Additionally, from a DDE perspective, we could ask whether the emergent alpha strike pattern tells a coherent story: does it reinforce the game’s intended theme, or create narrative dissonance? DDE invites us to treat that breakdown not just as a balance issue, but as a story problem—a failure of the antagonist dynamic to challenge the player in a satisfying way.

So What?

“When you start looking at a problem and it seems really simple, you don’t really understand the complexity of the problem. Then you get into the problem, and you see that it’s really complicated, and you come up with all these convoluted solutions. That’s sort of the middle, and that’s where most people stop…

But the really great person will keep on going and find the key, the underlying principle of the problem — and come up with an elegant, really beautiful solution that works.”

—Steve Jobs

Jobs’s quote has been a key insight in my work as a learning professional when confronted with complex problems and I think it has relevance here. I'm only just beginning to apply these frameworks to my own design thinking; I’m not claiming mastery. But I see value. MDA and DDE give me a language—not just to reflect on why a rule feels off, but to articulate what it’s doing and how it might change.

They don’t hand you answers. But they do help you ask better questions. For anyone working on rules or scenarios, or trying to understand why a game did or didn’t land, that’s a solid starting point.

As with many things, arriving at the right solution begins with ensuring we're asking the right questions. And DDE, in particular, gives us permission to look at rules, visuals, stories, and player feelings as all part of a cohesive experience. It encourages a holistic mindset that sees tabletop wargaming not just as rules resolution, but as designed experience—where every roll of the dice contributes to the story we’re telling together on the table.

References

Hunicke, R., LeBlanc, M., & Zubek, R. (2004). MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research. Proceedings of the AAAI Workshop on Challenges in Game AI. Retrieved from https://www.cs.northwestern.edu/~hunicke/MDA.pdf

Walk, W., Göbel, S., & Effelsberg, W. (2017). Design, Dynamics, Experience (DDE): An Advancement of the MDA Framework. In F. Nacke et al. (Eds.), Game Dynamics (pp. 27–45). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-53088-8_2

Walk, W. (2015). From MDA to DDE: Necessary Enhancements on a Commendable Design Framework. Gamasutra (now Game Developer). Retrieved from https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/from-mda-to-dde

Wittgenstein, L. (1921). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Aboleth Overlords. (2024). MDA for Tabletop Adventure Games. Retrieved from https://aboleth-overlords.com/2024/04/17/mda-for-tabletop-adventure-games/

Carroll, J. (2013). Using the MDA Framework as an Approach to Game Design. Medium. Retrieved from https://medium.com/@jenny_carroll/using-the-mda-framework-as-an-approach-to-game-design-9568569cb7d

First Person Scholar. (2014). A Working Theory of Game Design. Retrieved from https://www.firstpersonscholar.com/a-working-theory-of-game-design/